Shrub-steppe: Deep Roots & Spring Flowers

Shrub-steppe plant structures reflect how they are adapted to their habitat and their relationships with other living things such as pollinators.

Spring is the most colorful season in the shrub-steppe when many plants take advantage of mild temperatures and seasonal rain to put forth flowers. As you stroll among the shrubs, bunchgrasses, and forbs (flowering plants) you may notice a variety of shapes and structures among the leaves and flowers. What drives all this diversity? If all these plants are adapted to the same conditions, why do they look so different?

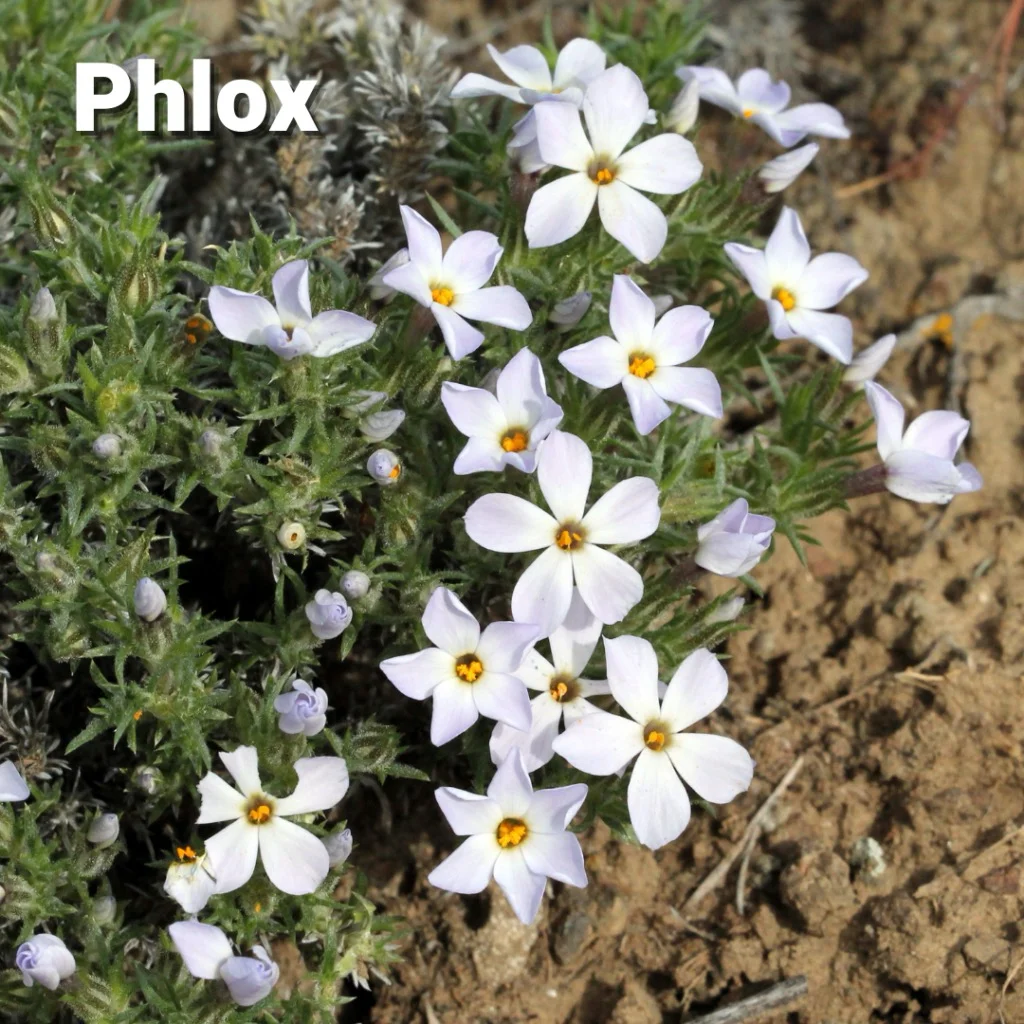

There’s more than one way to survive in this windy, dry habitat! Phlox and balsamroot keep their leaves low to the ground. Bitterroot has fleshy leaves that store water early in the spring, then die back before the flower emerges, storing energy in its thick root. Many plants such as fiddleneck and globemallow have a fuzzy surface on their leaves and stem that trap moisture, and some, like sagebrush and rabbitbrush, have narrow leaves to reduce the surface area exposed to the sun. If you could see into the ground to the roots of these plants, you would find a system that reaches deep for moisture, some with thick taproots to hold them steady in the wind.

Flowers are shaped by the plant’s relationship to one specific part of its environment: the pollinators that help transfer genetic material from one plant to another. A flower’s structure, color, bloom time, and even scent are linked to these other living things, sometimes very specific ones. Warming temperatures in the spring allow insects such as bees and butterflies to emerge and look for food, so many plants in the shrub-steppe bloom during this time. Spring flowers with a wide bowl shape such as bitterroot and globemallow attract insects of many sizes and have pollen that clings to insects’ bodies as they move around inside the flower. A flat-shaped flower head like balsamroot also allows many different kinds of pollinators to visit, and even a beetle stumbling around will likely drop some pollen in the right place. Other plants are more limited in the pollinators they’ll attract. Fiddleneck has a spiral of yellow flowers, too little for any but the smallest bees to enter. Luckily there are hundreds of species of native bees, ranging in size from a few millimeters (mason bees, sweat bees) to two centimeters long (bumblebees.) Trumpet-shaped flowers like phlox have wide petals to show off, but the nectar is hidden down a narrow tube. Only long-tongued insects like butterflies can reach it, and they contact the pollen-producing and pollen-receiving flower parts as they sip. Lupine flowers have a unique shape, with the pollen hidden inside folded petals. As bees visit, they are heavy enough to push the lower petals down, causing the flower’s stamen and pistil to push up between the folds and contact the bee’s fuzzy body. Only heavy bees are rewarded with nectar as they pollinate this flower.

Why is it important to know a plant’s pollinators? They are essential for helping a plant make seeds and reproduce. The preserved shrub-steppe within the Hanford Reach National Monument is important bee habitat and is the site for a pollinator study published in 2018. The study found eighteen different types of bees along with butterflies and moths visiting flowers on the Hanford site. Knowing more about the relationships between plants and insects will help us know more about the entire food web around us.

Learning about different types of seeds is another way to get to know our plant neighbors.

Activities

Bitterroot Coloring Page – Shows the large root of the bitterroot plant

Phlox Flower Anatomy Coloring Page – Learn more about flower anatomy